Chanukah 5784 COMPLETE STRAIGHT TEXT Divrei Matir Asurim (for easier copying to email)

REVISED straight text version substitutes “YHVH” for Hebrew four-letter name of God (inadvertently included on one page of earlier version — apologies)

Chanukah 5784 COMPLETE FORMATTED Divrei Matir Asurim (formatted for printing or reading on-line)

REVISED formatted version substitutes “YHVH” for Hebrew four-letter name of God (inadvertently included on one page of earlier version — apologies)

Note: the substitution of English for the four-letter Hebrew name of God is also made below, as of Dec 15. Thank you to the reader who pointed out this editing error, which makes printing and sharing of document problematic in places where proper disposal of sacred text is not easy. Please advise of any other editing or content issues with Divrei Matir Asurim.

This Divrei Matir Asurim is part of a continuing experiment in sharing General Meeting and Team news with inside members and share inside members’ thoughts with outside members. This material is available in three formats: straight text for copying into emails; formatted text for copying/printing for postal mail; and on-line in hypertext (with some internet links for those who can access them, below).

INTRODUCTION and CONTENTS

This is a special, news-less edition of Divrei Matir Asurim for Chanukah (spelled many ways, plus Khanike, in Yiddish). This edition includes resources from “A Hanukkah mailing for Jews Across and Beyond Bars” (5783) and a few new items for 5784.

8 Meditations for 8 Nights by Chaplain Julie

Khanike: A Portal to Abundance by Callie Ryan

Practice, Custom, and Questions for Chanukah Lighting

Exploring “A Little More Darkness” based on an essay by Kendra, Student Rabbi

Genesis: Adding Darkness

Unless otherwise noted, material is the work of V. Spatz, editor of Divrei Matir Asurim. For accessibility and ease of emailing, there is a straight text version of this edition as well.

More monthly operations notes and new Torah Explorations are planned. Our Resources Team is also considering new, less time-sensitive publications around Jewish values. Your own Torah, written words or easily reproducible visual arts are welcome. We’d also love to know your responses to what we share.

Contact us through your outside MA pen pal, if you have one; through USPS mail directly to: Matir Asurim, PO Box 18858. Philadelphia, PA 19119; or by emailing matirasurimnetwork@gmail.com.

Blessings for Chanukah

Blessed are You, Divine Presence, Our God, Breath of all the Universe, who makes us holy with commandments to kindle lights of Chanukah.

Bruche ateh Shekhinah Elot’heinu Ruach haOlam asher kidshatnu bmitzvoteihe vetzivatnu l’hadlik ner shel Chanukah.

Blessed are You, Divine Presence, Our God, Breath of all the Universe, who made miracles for our ancestors in past days at this season.

Bruche ateh Shekhinah Elot’heinu Ruach haOlam, she-asteh nisim l’kodmeinu ba-yamim ha-heimen ba-z’man ha-zeh.

Hebrew from Non-binary Hebrew project. Translation from Matir Asurim.

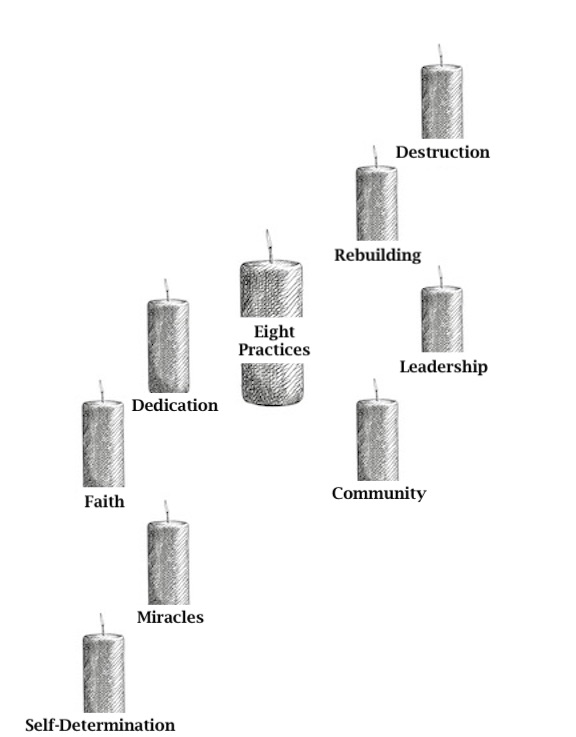

8 Meditations for 8 Nights

by Chaplain Julie

Chanukah is a time to connect with the Creator of Light, the light within us, and the light of the world. The holiday is a reminder to take spiritual actions that will dispel the darkness of the world with light.

Here are eight practices for creating more light in the world:

1. Destruction: Sometimes things and relationships are destroyed. Sometimes we are the destroyer, the victim or simply the witness, and sometimes all three. From destruction we notice impermanence, fragility, pain, release, joy, liberation or even death. After the Temple was destroyed, there was still hope for the Jewish people.

Spiritual Action: Take an honest assessment to witness what has been destroyed.

What feelings come up when you think about the destruction?

2. Rebuilding: After assessing the destruction, we have the opportunity to rebuild in body, mind and spirit. No matter how big the damage is, with dedication, perseverance, and effort, we can rebuild with loving intention. Rebuilding faith and community was achieved after the Temple’s destruction.

Spiritual Action: What has been destroyed that I want to see rebuilt?

What are some realistic steps to take to begin the rebuilding process?

3. Leadership: Courage and focus can help get us through dark times. Being a leader who brings about change requires empathy, communication, good decision-making, and resilience. Like the shammash or helper candle on the menorah, as leaders we can serve others to help increase their light and ours, as well.

Spiritual Action? What do I stand for, and how can I show my leadership?

Make a list of the values or core beliefs you are passionate about. What are some ways that people will see your behaviors and actions in alignment with your values and beliefs?

4. Community: There is a power in numbers. We are stronger together. Community reminds us that we’re never truly alone. Together, we can accomplish great things, like advocating for change or rebuilding after destruction.

Spiritual Action: Who are the people you feel safest with, and how can you nurture these relationships?

Do something kind someone you are grateful for.

5. Dedication: Dedicating yourself to something can help connect you with the Source of Light and give you a sense of purpose. The lesson of Chanukah is to be proud of who you are. There is nothing wrong with having pride in your work or being proud of yourself. Know that you matter, and your time, energy and intentions are sacred. The word Chanukah means dedication because when the Maccabees (the Jewish fighters who led the revolt) overcame Greek oppression, they rededicated the Second Temple and themselves to Jewish ideals.

Spiritual Action: What gives your life meaning?

Dedicate a task to make it special in honor of someone you respect. Consider how you can have a positive impact for yourself, your family and your community.

6. Faith: When we have faith, we can change the world. Faith in ourselves, faith in humanity, faith in the Source of Light. Faith is complete trust or confidence. The Maccabees had faith that they could fight the most powerful army of the ancient world, and you can do hard things, too! Faith can carry us through transitions and difficult times.

Spiritual Action: What would you like to have more confidence or trust in?

Offer a prayer or meditation to call in more faith around something you’re hoping for.

7. Miracles: A miracle can’t be explained by science or natural law. Miracles are beyond reason and transcend limitations. To experience a miracle is to believe in the Great Mystery that anything is possible, like the Chanukah story of the oil that miraculously lasted for eight nights. Just like this small but mighty amount of oil, how can we stretch ourselves to do good in the world and trust that goodness will also come to us?

Spiritual Action: Noticing the blessings that come your way, like sparks of light, what are some miracles that you’ve experienced in your life?

Make a gratitude list of big or small miracles that you’re grateful for.

8. Self-determination: Chanukah is a celebration of religious freedom and self-determination. It’s a reminder for us to consider the ways in which we advocate for and take care of ourselves, especially in the face of hardship. Some even say that more important than the miracle of the oil, the Chanukah message of winning the war against the Greeks because of self-determination is the greater story. Self-determination means you have a strong sense of your strengths, needs and interests, as well as your limitations. It comes with a good sense of self-confidence and self-esteem, which isn’t always easy for someone who’s been fighting oppression and oppressive systems for a long time.

Spiritual Action: What are your strengths and limitations, and how can you use those to advance towards your goals?

Originally appeared in Matir Asurim’s Chanukah Resources 5783.

“Khanike: A Portal to Abundance”

by Callie Ryan

Originally appeared in Matir Asurim’s “A Hanukkah mailing for Jews Across and Beyond Bars” 5783 (2022)

This entire piece was originally presented in handwriting with drawings. See original booklet for the graphic version.

While Khanike is often acknowledged as a festival of lights, I also like to think of it as a portal into a quiet, warm, and comforting space which leaves room for deep internal cultivation allowing us to EXTEND ABUNDANCE outwards to our spiritual and physical community members. With this extension we are also able to fill our insides with the fire of care work, passion, and resilience. Khanike — as an opportunity to literally and/or conceptually light our way alongside one another into an exploration of what is and what is possible.

How do we feel connection to one another during times of isolation and how do we honor this time of both easing the darkness and coolness of winter as well as breathing light into the pathways ahead which are flooded with UNCERTAINTY and shadows. Inspired by tenants of both Kabbalah and Daoism,* we honor that in the space of UNKNOWN and RICH EMPTINESS there is abundant room for spontaneous fluidity, dreams, and growth — the sacred balance between form & force, emptiness & fullness, warmth like cinnamon, melting softness like butter, sweetness and stickiness as flexible and as strong as honey — together we explore the spectrum between lightness and darkness.

On these nights of Khanike, we do not need physical candles to know what we are dreaming alongside one another in ritual, in care, in comfort, discomfort, in fear, in joy, in grief, in solace, in the changing of the seasons, in the presence of all earth and G-d’s elements alive and flowing through the vessels and

pathways of our beautiful physical vessel/container storing our bright and abundant spirits. This divine ebb and flow that lives within us will warm and light our path as we swim into this sacred time of stretching, of dreaming, of reflecting, of light turning to darkness and darkness turning to light — in beautiful timelessness and interdependence. Honoring all that you are and all that we are together. We do not need physical dreidels to spin like them, to play like them, to spread that delightful spontaneous movement which has acted as a source of strength, bliss, and silliness for our ancestors and loved ones past, present, and forever stretching into the beyond. Let us spin like dreidels into this time of abundance and supported-reflection…hands embraced, arms outstretched with love and warmth.

*Inspired by Chapter II of the Dao DeJing by Lao Tzu:

The vessel and the emptiness within the vessel are all sacred and necessary.

Practice, Custom, and Questions for Chanukah Lighting

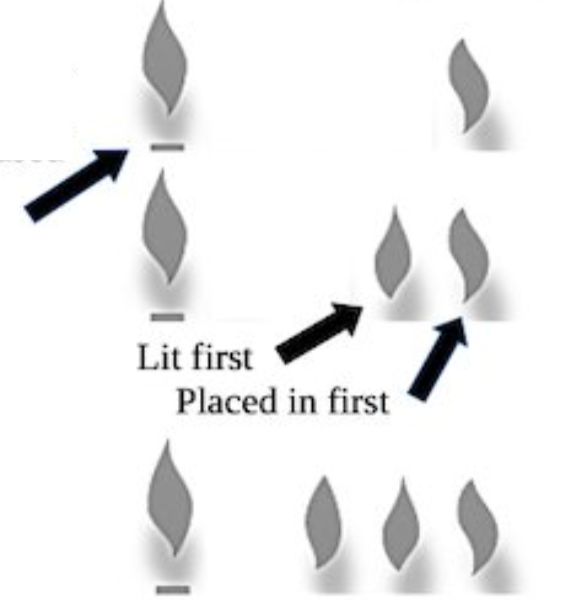

Candles for the nights are placed in the menorah beginning on the right.

In Ashkenazi practice, the “shamash[helper]” is lit first and that is used to kindle the candles for each night. After its use in lighting other candles, the shamash is placed into the menorah, often at the center.

First night, there is one candle, farthest right (plus shamash).

On the second night, two candles are placed beginning on the right.

Then, the “newer” candle, is lit first, using the shamash.

One teaching says that placing the “older” candle first honors the past, while reaching first to the “newer” candle honors the future.

Settled Answers and Multiple Practices

Many details of celebrating Chanukah raised questions, beginning long ago and continuing today.

Some have long-settled answers in one community and different settled answers among another group.

Common rituals can be a comfort. But so can knowing that Judaism has always had many different ideas about fulfilling commandments and many different ways of adapting to changing circumstances.

Sometimes reasons given for a “right” practice tell us a lot about what mattered to a particular community. Sometimes, the questions themselves are key:

Is the point

— to perform the lighting?

— to witness the lights for ourselves?

— to show the lights to others?

(“publicizing the miracle”)

Is the whole thing about light and darkness?

Or is it to mark the days?

How much is enough?

One ancient argument asks whether each person should light their own or whether one per “household” is sufficient….perhaps better.

Do we “beautify” a commandment by doing more of of it?

Is the common nature of a joint ritual a different kind of “beauty”?

How does the Jewish value of protecting the Earth and not wasting affect choices about

what, and how much, to light?

Exploring “A Little More Darkness”

Based on “A Little More Darkness,” by Kendra, Student Rabbi 5783 (2022)

The holiday of Chanukah is newer than the Hebrew Bible. There are no biblical instructions for how to observe the festival, so the ancient rabbis had to decide what to do. They knew the start date: 25 Kislev. And they knew the festival should last eight days, to remember a “miracle of eight-days’ light.” At the Temple’s rededication, a small bit of oil, just enough for one day’s light, lasted for a full eight-day ritual. But how, exactly, should we mark the eight days of light?

One school, Beit Shammai, said:

- Start with eight candles on the first night;

- reduce each night,

- until only one light is left.

Another school, Beit Hillel, said:

- Begin with one light on the first night;

- add one more each night,

- until eight burn on the last night.

The practice for 2000 years has followed Beit Hillel. But an essay published last year, just before Chanukah, inspired some Jews to try Beit Shammai’s way of lighting.

Kendra wrote:

“I love the dark, thanks in no small part to my astronomer grandfather. I have fond memories of setting up telescope equipment in fields and forests, accidentally getting my fingerprints all over lenses and chroma filters. I love the way darkness calls us to a deepened sense of awareness and holds the possibility for restoration. It was in the dark that I learned how to listen and feel my way through the world around me. This love for the dark helps me find meaning in winter’s long, chilly nights.

“Darkness gives cover. Darkness is transition. Darkness is magic.

“…All year round, but especially in winter, we are bombarded, with calls to seek out light and to banish darkness. And frankly, I’m not interested. As with all things, race makes itself known in our language and symbolism. For centuries, white supremacist logic has tried to convince us that all that is right is white and light, and that darkness is void and ungodly. And yet, I carry a deep knowing in my body that that could not be further from the truth.”

The essay goes on to quote Rev James Cone (1938 – 2018), a Christian scholar, who wrote A Black Theology of Liberation. Liberation Theology centers perspectives and needs of oppressed people. In his 1970 book, Cone urged theologians to stop talking about liberation in abstract ways, ignoring realities for black communities within “white racist society”:

“Theology cannot be indifferent to the importance of blackness by making some kind of existential leap beyond blackness to an undefined universalism. It must take seriously the questions which arise from black existence and not even try to answer white questions, questions coming from the lips of those who know oppressed existence only through abstract reflections.”

Kendra shared the quote above and continued:

“For me, taking my own Black existence seriously means that it is not enough to rely on universal metaphors for light during this time….we have got to attune ourselves to different ways of thinking about the dark, keeping blackness at the center.”For me, taking my own Black existence seriously means that it is not enough to rely on universal metaphors for light during this time….we have got to attune ourselves to different ways of thinking about the dark, keeping blackness at the center.

“Darkness is as old as G!d G!dself. Above us at night and below us in the depths of the oceans and the earth’s layers, darkness is always with us, thank G!d, and it is teeming with life and possibility.”Darkness is as old as G!d G!dself. Above us at night and below us in the depths of the oceans and the earth’s layers, darkness is always with us, thank G!d, and it is teeming with life and possibility.

“This year [2022], in a celebration of a thick, rich, overflowing darkness, I will be lighting my Chanukiah in the tradition of Beit Shammai; beginning with eight candles, and welcoming a little more darkness each night.”

Following Kendra’s example, a number of Jews adopted the Beit Shammai practice last year.

As with most Jewish practice, there are many ways to understand and experience the “adding darkness” way of approaching Chanukah. Jews who are not Black do not share the same “deep knowing in [one’s] body” that Kendra describes. But we can all learn “different ways of thinking about the dark, keeping blackness at the center.”

We cannot know, yet, how those shifts in thinking might influence Jewish communities far down the road. But we can explore, together, a “celebration of thick, rich, overflowing darkness.”

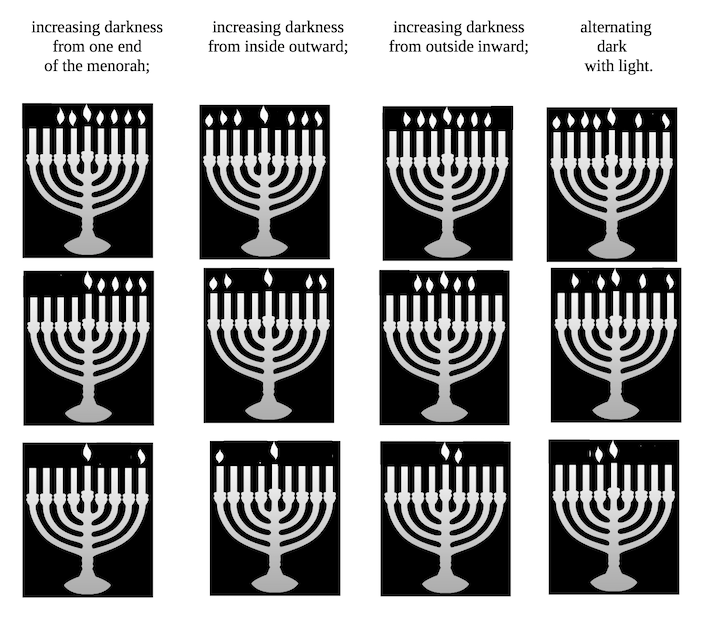

How do we add darkness?

We don’t have centuries of teaching explain exactly how to increase the dark from one night to the next.

There are many possibilities, with a variety of reasonings and intentions. Below illustrates how several methods of adding darkness appear on the 3rd, 5th, and 8th nights of Chanukah. In each case, practice moves from zero units of darkness and eight lights (plus shamash [helper]), to seven units of darkness and one light (plus shamash). The darkness grows in different patterns, however:

Which lights do we set up first? Which are lit first? What is the order of adding darkness?

increasing darkness from one end of the menorah;

increasing darkness from inside outward;

increasing darkness from outside inward;

alternating dark with light.

Where candles are not available, filling in with pen/pencil, or covering over one light, each night could be part of an experiment in lighting in the tradition of Beit Shammai.

1) Zero units of darkness — 8 lights (plus shamash)

2) One unit of darkness — 7 lights (plus shamash)

3) Two units of darkness — 6 lights (plus shamash)

4) Three units of darkness — 5 lights (plus shamash)

5) Four units of darkness — 4 lights (plus shamash)

6) Five units of darkness — 3 lights (plus shamash)

7) Six units of darkness — 2 lights (plus shamash)

8) Seven units of darkness — 1 light (plus shamash)

What other ways can we seek to “welcome a little more darkness each night“?

————————————————————————–

Genesis: Adding Darkness?

In the Book of Genesis, God communicates with many characters. Sometimes directly. Sometimes through messengers. Sometimes in dreams. This changes over the course of Genesis, with God’s communication become less direct. In Eden, little is left to the imagination — God even talks to the snake. In the final chapters of Genesis, God is no longer speaking directly. Joseph does not seem to experience God as more distant than his ancestors did, but there is more for him to puzzle out

This is little like the mystical concept of “tzim-tzum,” which says that God first filled up everything so there was no room for Creation and then contracted, kind of squished Godself, so the world could exist. In a similar way, Genesis starts out like a bright space, without shadows, and gradually adds darkness, leaving more blanks for people to fill in. Everything is spelled out for Adam and Eve. Joseph has to interpret how divinity works in his life. The growing darkness of Genesis reflects increasing room for us — as individuals and in community — to explore our own interpretations.

ONE: God hangs out in the Garden of Eden, speaks to all

In early chapters of Genesis, God speaks directly with Adam, Eve, the serpent, and Cain. In addition, God walked in the garden with Adam and Eve: “They heard the sound of God YHVH moving about in the garden at the breezy time of day…” (Gen 3:8).

TWO: God talks to Noah and family

God speaks directly with Noah, before the Flood, and with Noah and sons afterward (Gen 6:13, Gen 9).

THREE: God communicates with Abraham (but not with Sarah)

God speaks directly with Abraham, beginning with “Go forth,” at Gen 12:1.

FOUR: Hagar and God communicate; Hagar names God

Hagar communicates with messengers of God, and she names “the God who spoke to her, God-who-Sees-Me” (Gen 16, 21; Gen 16:13).

FIVE: God speaks once to Isaac

Although God speaks directly with Abraham many times, God speaks directly with Isaac only once: “That night YHVH appeared to him and said, ‘I am the God of your father Abraham. Fear not, for I am with you, and I will bless you and increase your offspring for the sake of My servant Abraham’” (Gen 26:24).

SIX: Rebecca and God speak directly once

Rebecca goes to “inquire of God” about her pregnancy, and God responds directly: “YHVH answered her, ‘Two nations are in your womb…'” (Gen 25:23).

SEVEN: Jacob’s communications with God take several forms

Jacob first hears from God in a dream (Gen 28:12-13); then wrestles with a divine being (Gen 32); and, finally, hears from God directly (Gen 35:9).

EIGHT: God does not speak directly with Joseph

The Torah includes no direct communication between God and Joseph. But Joseph interprets dreams and his own life in ways that seem to understand God’s intentions.

Joseph says his dream interpretations are from God (Gen 41:16). He tells his brothers that God planned everything — his bondage, imprisonment, and eventual service to pharaoh: “…it was to save life that God sent me ahead of you” (Gen 45:5).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

“Ode to Dirt”

Dear dirt, I am sorry I slighted you

I thought that you were only the background

for the leading characters—the plants and animals and human animals.

It’s as if I had loved only the stars

and not the sky which gave them space

in which to shine….

— from “Poem 134: Ode to Dirt” by Sharon Olds, from Odes (Knopf, 2016)

Sharon Olds is a poet and professor with many publications and awards. Her first poetry book was published in 1980; her most recent, Balladz — focusing on communal grief and COVID — was published in 2022. She is a professor of creative writing at New York University and helped found writing workshops for military veterans at NYU’s Coler Hospital.

Before the Narrow Bridge

A very popular teaching comes from Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772-1810):

“The whole world is a very narrow bridge. The essential thing is to not be afraid.”

This is found in a publication called Likutei Moharan,** and it appears in different versions, depending on how the Hebrew is translated.

The narrow bridge teaching has been made into popular songs and inspired visual arts, as well as much discussion over the centuries. The longer text which includes this line doesn’t get as much attention. But it seems appropriate to this particular season.

The section is about challenges that meet a person who is trying to keep to what they think is right and hoping to increase their spirituality. Rabbi Nachman writes:

“A person needs tremendous determination to be strong and courageous.”

It is common to “experience falls, descents, confusions and so on,” he continues. But a person must do “theirs.” Literally: “he must do what is his.”

“And know! each time you detach and shift just a bit from materialism to divine service, all the movements and changes accumulate, combine and bind together, and come to your aid at a time of need—i.e., when there is, God forbid, any trouble or misfortune.

“Know, too! a person must cross a very, very narrow bridge. The main rule is: Do not be frightened at all!” — Likutei Moharan, Part II Torah 48:2, trans., Moshe Mykoff, Breslov Research Institute

What does it mean for a person to do what is “theirs”? Some teachers stress Jews must keep a kosher diet, recognize Jewish time, and perform prayers and ritual as their tradition sets out. Others stress that it is every Jew’s “job,” in a sense, to do whatever thing they can to make the world a better place.

Not everyone is prepared to be an emergency first responder or teach elementary school, for example. Most of us are not in a position to intervene in terrible world conflicts or influence public policy. But Rabbi Nachman reminds us that we can refocus our attention right in front of us: We can be kind to someone suffering, reach out to someone we have hurt or ignored, clean up our little corner of the world. It may seem small. Even insignificant. But trying to attack problems we cannot solve only exhausts us.

Focusing on what is “ours” to do can help prevent hopelessness and despair. And one lesson of Chanukah is that we can start with a little — light or darkness — and watch it grow.

Chag Chanukah Sameach — a joyous Chanukah