Divrei Matir Asurim is designed to help share General Meeting and Team news with inside members and share inside members’ thoughts with outside members. This material is available in three formats: straight text for copying into emails; formatted text for copying/printing for postal mail; and on-line in hypertext (with some internet links for those who can access them; below). This is still an experiment. Feedback welcome.

Kislev 5784 COMPLETE STRAIGHT TEXT Divrei Matir Asurim (for easier copying to email)

Kislev 5784 COMPLETE FORMATTED Divrei Matir Asurim (formatted for printing or reading on-line)

Divrei Matir Asurim is divided into two sections this month, to make it easier to share one section, and not the whole, with penpals or others who might be interested.

- Meetings and Operations

- Torah Explorations — Tent Meditations by Rabbi Yael Levy. Forks in the Genesis Road and more

Inside readers, please send responses to news shared here, additional thoughts on MA operations, or Torah Explorations: through outside MA pen pal, if you have one; through USPS mail directly to: Matir Asurim, PO Box 18858. Philadelphia, PA 19119; or by emailing matirasurimnetwork@gmail.com.

MEETING AND OPERATIONS

Recent General Meeting News

Matir Asurim held a general meeting on October 25 and a small-group check-in on November 8. There is no meeting on November 22, due to Thanksgiving holiday in the U.S.

Many active members are engaged in urgent Israel/Palestine-related work at this time, which is shifting availability for meetings and other work. Two topics raised for future discussion: 1) Paid staff, to help sustain Matir Asurim over the long-haul, especially when a crisis takes volunteer energy in other directions. 2) Making room for a range of opinions on Israel/Palestine, as this crisis continues to affect members, inside and outside.

Team and Working Group News

Membership and Wellness:

MA’s two listservs for outside members need some updating. Members volunteered to contact existing members and new people interested in joining.

Finance and Fundraising:

We haven’t done a fundraising campaign at all this year. Possibility of doing that was raised in October, but no plans yet.

Individual support:

One individual released from custody and seeking housing and other support outside. Educational and networking connections evolving for others.

Penpal:

Question/suggestion about creating sample letters to help larger numbers of people write messages in a future event, like the Rosh Hashanah letter-writing earlier in the fall.

Communications:

We are still working to improve website for accessibility and focus of message. Outside organizations are now invited to share information and events through a “News from our network” form. These notes can be shared in E-news.

NEXT GENERAL MEETING: December 13

——- Memorial, Healing and Special Concern, Celebration ——-

Yahrzeits:

11/17/1992. Audre Lorde. Caribbean-American poet, author, and political activist

11/26/1985. Vivien Thomas, Pioneer in cardiac surgery (medical assistant, with high school education)

11/29/1980. Dorothy Day, Journalist and social activist, founder of The Catholic Worker newspaper

12/4/1993. Frank Zappa. US musician, composer, songwriter, producer, and director

12/7/1970. Rube Goldberg. Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and inventor (see also below)

Recent Execution Loss:

November 9: Brent Brewer, Texas

Executions Scheduled:

November 16: David Renteria, Texas

November 16 : Casey McWhorter, Alabama

November 30: Philip Hancock, Oklahoma

Healing and Special Concern: Displaced, injured, and frightened people, and all suffering from violence in any form. All who grieve and mourn the lost.

All lacking community. All seeking comfort amid community and interpersonal conflict.

All who seek healing of spirit; those needing medical attention and healing of body.

[Image: series of lighted memorial candles; borrowed from Hadar publication]

Celebration: One Matir Asurim member was released from detention. Members continue to support one another and celebrate joys of life and relationships amid much grief and confusion.

Share your prayer concerns, celebrations, and memorials for future editions.

Submit through an outside penpal, email ethreporter at gmail.com,

or mail to Matir Asurim, PO Box 18858. Philadelphia, PA 19119

TORAH EXPLORATIONS

Study and Struggle

As we enter the third month of 5784, the challenge for Jewish teaching, and our collective spiritual care, is enormous. Jews and all concerned for Israel/Palestine are mourning, praying, and organizing response — sometimes in opposition to one another. Many communities are experiencing conflict. Some personal relationships are stressed, due to war and associated politics. Meanwhile, our individual struggles and communal cares continue… with many of us feeling worn out and distracted, even less able to cope.

Just when we need Jewish community and traditions most, making those connections can be harder. Groups and resources that we once found comforting might be too focused on world events to meet our needs. Prayers or songs we used to appreciate might seem wrong to us in the current political climate. Maybe we feel less welcome in Jewish spaces because our views don’t match the majority. Or maybe we feel less safe in non-Jewish spaces because of our Jewish identity. And/or maybe we’re just confused.

So much of the Bible and later Jewish text focuses on “the Land,” biblical promises about who belongs where, and stories about conquering existing people and property. How do we learn timeless messages from sacred text that is part of active political, and military, conflict? How do we understand — and should we respond — when Jews use text to support political positions we oppose?

Some of us have been struggling with these issues for years, maybe decades. Some of us are new to questions about “the Land” and Torah. But all of us, Jews and others who take inspiration from Torah, are in this together now.

What kinds of spiritual resources would be most helpful at this time? Are there other materials that could help make sense of current events and their impact on Jewish communities around the world? Maybe Matir Asurim can facilitate access.

Do you have thoughts, prayers, concerns to share?

Please let your MA penpal know, or contact: Matir Asurim, PO Box 18858. Philadelphia, PA 19119; or by emailing matirasurimnetwork@gmail.com.

Genesis Portions by MONTH

Hebrew title [English], chapters: verses, Civic & Hebrew calendar dates for Shabbat the portion is read.

TISHREI (Sept 16 – Oct 14)

Breishit [In the beginning]. Gen 1:1-6:8. Oct 14. 24 Tishrei

CHESHVAN(Oct 15 – Nov 13)

Noach [Noah]. Gen 6:9-11:32. Oct 21. 6 Cheshvan

Lekh-Lekha [Go forth]. Gen 12:1-17:27. Oct 28. 13 Cheshvan

Vayera [He appeared]. Gen 18:1-22:24. Nov 4. 20 Cheshvan

Chayei Sarah [Life of Sarah]. Gen 23:1-25:18. Nov 11. 27 Cheshvan

KISLEV (Nov 14 – Dec 12)

Toldot [Generations]. Gen 25:19-28:9.Nov 18. 5 Kislev

Vayetzei [He went out]. Gen 28:10-32:3. Nov 25. 12 Kislev

Vayishlach [He sent]. Gen 32:4-36:43. Dec 2. 19 Kislev

Vayeishev [He settled]. Gen 37:1-40:23. Dec 9. 26 Kislev

TEVET (Dec 13, 2023 – Jan 10, 2024)

Miketz [After]. Gen 41:1-44:17. Dec 16. 4 Tevet

Vayigash [He approached]. Gen 44:18-47:27. Dec. 23. 11 Tevet

Vayechi [He lived]. Gen 47:28 – 50:26. Dec. 30. 18 Tevet

The Book of Exodus starts with Shemot [Names]. Ex 1:1-6:1. Jan 6, 2024. 25 Tevet.

——- —————————- ——-

TORAH EXPLORATIONS: Tent Meditations by Rabbi Yael Levy**

“Open Tent”

— by Rabbi Yael Levy, used with permission

It is so difficult to know what to say, to find words to speak into the sadness, turmoil and pain.

In the portion Lekh-Lekha [Go forth], the Infinite Mystery called: Go. Leave. Explore. Become.

In the portion, Vayera [He appeared], the Mystery calls: Sit. Be still. Be with. Notice.

Avraham sat among the trees

At the opening of the tent,

He lifted his eyes

And saw the Infinite Presence

Within all.

He saw that the Infinite Presence

Is within promise, hope, turmoil and pain.

The Infinite Presence is in conflict and longing.

The Infinite Presence is in

Grief, devastation and despair.

And the Infinite presence is in

Possibilities for healing and transformation

Not yet seen or imagined.

This awareness filled Avraham

And he rose to meet whatever life would bring

With humility and strength

What can help us sit in the grief, sorrow

And chaos of these days?

What can help us rise into each moment?

I find inspiration and comfort in this teaching from Etty Hillesum:**

“And you must be able to bear your sorrow; even if it seems to crush you, you will be able to stand up again, for human beings are so strong, and your sorrow must become an integral part of yourself; you mustn’t run away from it.

“Give your sorrow all the space and shelter in yourself that is its due, for if everyone bears grief honestly and courageously, the sorrow that now fills the world will abate. But if you do instead reserve most of the space inside you for hatred and thoughts of revenge—from which new sorrows will be born for others—then sorrow will never cease in this world.”Give your sorrow all the space and shelter in yourself that is its due, for if everyone bears grief honestly and courageously, the sorrow that now fills the world will abate. But if you do instead reserve most of the space inside you for hatred and thoughts of revenge—from which new sorrows will be born for others—then sorrow will never cease in this world.

“And if you have given sorrow the space it demands, then you may truly say: life is beautiful and so rich. So beautiful and so rich that it makes you want to believe in God.”

May we find moments of love and connection that help us bear our sorrows. May we have moments when we lift our eyes and can sense that the Infinite Mystery is sitting here with us, holding us all with compassion and care. — Rabbi Yael

“Sarah’s Tent”

— by Rabbi Yael Levy, used with permission

Nestled among ancient trees,

Adorned with threads of blue, crimson and violet

Sits Sarah’s tent.

The door is open.

Let us bow and enter.

As we do

A warm radiance envelops us.

We sit and the earth meets us with a gentle embrace.

As our eyes adjust to the tent’s darkness

We notice the presence of ancestors,

Ancient teachers and guides,

Some we recognize

And many whose names we do not know.

Welcome, they say.

We are grateful for you.

Their light surrounds us with loving care.

Gently they ask,

What prayers are upon your heart?

What are you holding?

What do you seek?

In response to our cries, confusion, fears and despair

They hold us close.

We will help you, they say.

Call upon us

With words, silences,

With songs, with tears.

We are always here.

And we will help you.

Call upon us.

May the love and strength of the ancient mothers hold and guide us all.

Divrei Matir Asurim gratefully shares, with the author’s permission, these meditations

associated with the portions Vayera and Chayei Sarah (See “Portions by MONTH“)

NOTES for Open Tent

Etty (Esther) Hillesum (1914-1943) lived her early life in Deventer, a small city in the Netherlands. Her mother, Rebecca Bernstein, was born in Russia and fled a pogrom, settling first in Amsterdam, where she taught Russian. Etty’s father, Dr. Levi Hillesum, directed a school focusing on classical languages. Her brother Jaap finished schooling very quickly, discovered new vitamins when he was 17 years old, and became a physician. Their brother Mischa was a pianist who performed Bethoven when he was 6 years old. Etty moved to Amsterdam when she was 18 and studied law and languages.

She wrote her diary while in a transit camp, where Jews were held until they were deported. She was murdered at Auschwitz in December 1943. The rest of her family were either killed at, or died in transit to, death camps.

Etty: The Letters and Diaries of Etty Hillesum, 1941-1943. Translator: Arnold J. Pomerans.

Wm. B Eerdman’s Publishing Company. Grand Rapids, MI, Cambridge, UK. 2002.

Yael Levy is founder and rabbinic director of A Way In, offering “a way in” to spiritual practice and awareness that uses the language of Jewish tradition and address universal issues. She is retired from a part-time position at Mishkan Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation in Philadelphia, and has worked with the Institute for Jewish Spirituality. She is an author and provides a mindfulness guide to the Torah portions of the week.

Contact: A Way In, P.O. Box 63912. Philadelphia, PA 19147-7779

Torah Explorations: Year-End and New-Year Recap

NOTE: Torah Explorations, unless otherwise noted, are from Virginia Spatz this month.

Last month’s Torah Explorations looked at the annual Torah reading cycle and how it fits with the fall holidays. Within a single holiday, we read the last lines of the Torah and then start at the beginning. One moment, forty long years of wandering are ending, Moses dies, and the people prepare to cross the River Jordan without him. The next moment, God is just beginning Creation, and the Exodus story, and then wilderness years, are many generations off in the future.

As the Torah closes, a whole generation has lived and died in the wilderness:

behind them: Mitzrayim, biblical Egypt, the narrow place where their people were enslaved;

ahead: the land YHVH [God] told Moses: “I swore to Abraham, and to Isaac, and to Jacob, ‘I will give it to your offspring'” (Devarim 34:4).

But the Jewish calendar doesn’t follow the people into that land. The bloody conquest stories of the next Bible books — Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings — are not the focus of our sacred reading cycle. Instead, ritual takes us from the river bank back to Breishit: “In the beginning…”

The Book of Genesis is full of narrative, rather than laws. And, as discussed in last month’s Torah Explorations, things move pretty quickly: In the first portion, we speed through Creation and the Garden of Eden to God regretting humankind and preparing to destroy everything. In just a few weeks, Eden, the Flood, and the Tower of Babel are already long past.

The Book of Genesis is divided into 50 chapters

and 12 weekly portions.

“Toldot [Generations]” is the sixth portion. It begins in Chapter 25.

With the new month of Kislev,

we hit the halfway mark in the Book of Genesis

Torah Explorations: Generations, Forks, and Unknowns

The first portion of Kislev, “Toldot,” starts out —

“These are the generations [eleh toldot] of Isaac, Abraham’s son. Abraham begot Isaac.”

— Genesis 25:19

If we’re new to the story, this doesn’t tell us much. If we’ve been following along from “In the beginning” — or if we’ve been around this bend before — we know who Isaac and Abraham are. But this is still a somewhat puzzling verse. And Divrei Matir Asurim has not looked yet looked at most of the Book of Genesis. So, this is a good place to pause and consider how the story got to this moment and whose story we are following.

Whose Story is This?

Just a few verses earlier, we read:

“These are the generations [eleh toldot] of Ishmael, Abraham’s son, whom Hagar the Egyptian, Sarah’s handmaid, bore unto Abraham.” — Genesis 25:12

Here, Ishmael’s mother, Hagar, is named. The text says she give birth to Ishmael.

…which might not seem extraordinary. But listing men and their sons, without mentioning the mothers, is common in the Bible. In fact, the Brown Driver Briggs biblical dictionary says:

“toldot. generations, especially in genealogies = account of a man and his descendants.”

So, on the one hand, Hagar is included, and given an active role, while Sarah (Isaac’s mother) is not. On the other hand, it is more common to NOT list the mothers; so naming Hagar, and making a point of calling her Sarah’s maid (or slave), marks her and Ishmael as unusual, outsiders.

Ishmael is called “Abraham’s son” — a sign of status equal to Isaac’s in some ways. But, Ishmael and Isaac are two forks in the Genesis road, and Ishmael’s is not the one the story will follow.

Reviewing previous forks in the Genesis road will help prepare us for continuing with Isaac’s story and the rest of the Kislev readings.

Forks in the Genesis Road

The Torah emphasizes some important points in its timeline through the use of tens: Ten generations between Eden and the Flood. Another ten after the Flood to Abraham and Sarah. All along, God and individuals make choices, with lasting consequences. But the tens highlight points of serious change:

(1) In the first generation

- Eve and Adam eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil;

- God ejects them from Eden and makes that garden paradise off-limits to humans forever;

- Adam and Eve work the land and have children, beginning human life beyond paradise

- — this includes a lot of loss, as one son, Cain, murders the other, Abel, and is then exiled

- — Eve and Adam have another child, Seth, and the generations of the main story line continue; Cain, under God’s protection, starts a family and founds a city, and drops out of the story.

(2) In the tenth generation

- God sees human wickedness, decides to blot out “humans together with beasts, creeping things, and birds,” but Noah “finds favor with God”;

- Noah, “blameless in his generation,” will survive the Flood, along with his household — sons: Ham, Japheth, and Shem (family women are not named) — and many animals;

- After all the destruction, God blesses Noah’s family, “Be fertile and increase, and fill the earth,” and also declares that “the devisings of the human mind are evil from youth”

- — God issues a rainbow sign and a new covenant, promising not to send another Flood

- — Noah tills soil, plants a vineyard, and gets drunk. Ham “sees his father’s nakedness,” while Japheth and Shem try to cover him; Noah curses Ham and blesses Shem and Japheth.

(3) After ten more generations

- Terah, the ninth generation in Shem’s line, leaves Ur of the Chaldees for Canaan. He travels with his son and daughter-in-law, Abraham and Sarah, and his nephew, Lot (the tenth generation). They get as far as Haran in Paddan-aram, settle there, and Terah dies.

- God calls Abraham, “Go forth from your native land and from your father’s house to the land that I will show you.” (Readers get no explanation as to why Abraham is called.)

- Abraham and Sarah (called by earlier names, Abram and Sarai) go forth. They experience difficult, sometimes violent, adventures and struggle to conceive children.

- — eventually, their children each experience near death, by what appears to be God’s command

- — the servant Hagar, and Ishmael, her son with Abraham, are cast out from the household and the main plot; “God is with” them, and their stories continue, but Genesis follows another line.

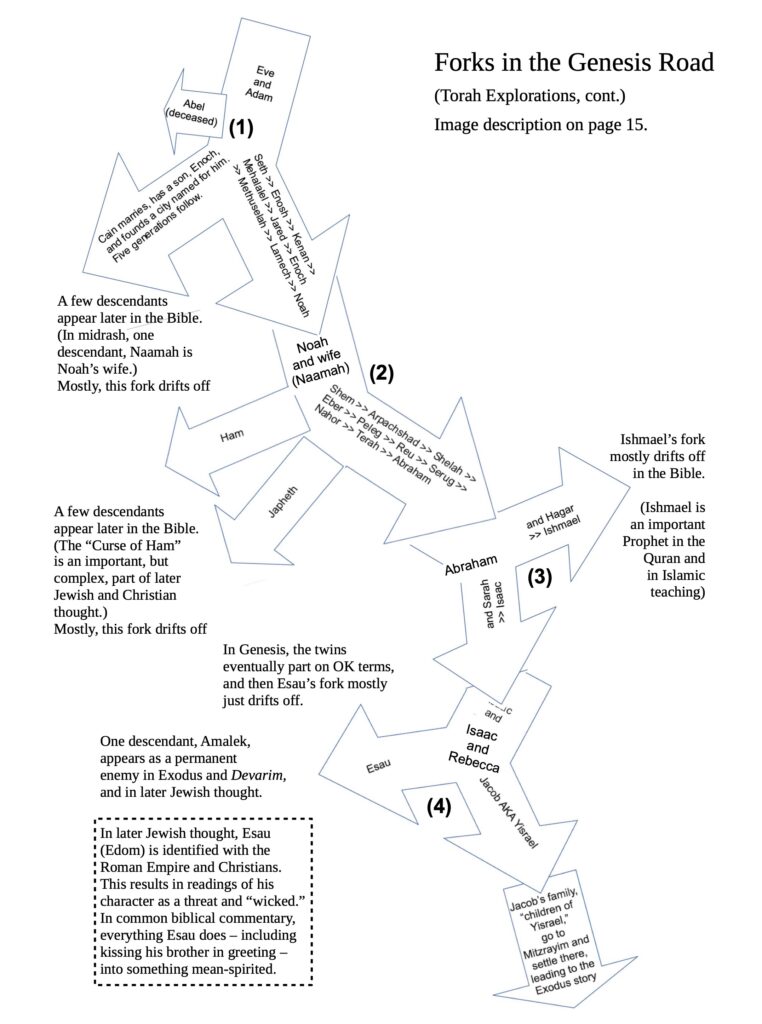

At each of these three points, the Torah follows one fork in the road, and leaves the others mostly alone. (For those who can receive and view graphics, the diagram near the end of this edition illustrates some Genesis family splits. Image description follows.) Genesis follows Seth and Shem and Isaac; the family lines of Cain, Ham, and Ishmael are dropped or de-emphasized. But it’s human nature to ask “what happened?” when we’re not told and to try to fill in the story ourselves. Jewish commentaries have always found a lot to discuss in what goes unsaid in the Torah — what tradition calls “white space” between the black ink of the scroll’s letters.

Dropped Forks

Some commentaries, over the centuries, treat the family lines that split off from the main Genesis story as problematic, even evil — sometimes equating biblical characters with real life enemies. But the text itself tells us that God protects Cain, blesses all the sons of Noah (even though Noah curses one) and blesses Ishmael, promising he will “be a great nation.”

Some Jewish commentary lifts up those from the “dropped fork” as kin, friends, and teachers. Here’s one example from Fork (1):

“In exile, Cain met Adam.

Adam asked: ‘What became of your sentence?’

Cain answered: ‘I repented and reached a settlement.’

Adam replied: ‘Such is the power of repentance, and I did not know!'”

– from Breishit Rabbah 22:13, 6th Century CE

Adam considers for the first time that he and Eve might have repented eating the forbidden fruit, launching a different path. Of course, in the Bible, God does not offer the couple that option. But Jewish tradition chooses to stress the power of change.

Questioning God, Filling in the “Why?”

Jewish commentary also questions God’s choices at various forks of the Genesis road. Throughout Genesis, God makes many judgments and issues punishments. But God’s reasoning is not always clear. We don’t know why God accepted Abel’s sacrifice and not Cain’s. God appears inconsistent in responding to evil of humanity: enacting terrible collective punishment with the Flood and then, seeing more human evil, promising no more Floods. (See also the story of Sodom’s destruction, Gen 18-19.)

So, Jews, and other readers, have to puzzle out what lessons we should learn in each situation.

For example, in Fork (3), the Torah does not say why, in Gen 12:1, Abraham was chosen and told to “Go forth.” Ancient teachers were not happy with this unanswered “why?” and suggested answers:

- Some invented a prequel to the story, describing Abraham’s spiritual journey before being chosen by God.

- Other teachers stress that Abraham later showed positive attributes, and we should copy those.

- Some suggest that he was no more worthy than anyone else, but God decided to develop a relationship with him, and that’s what countsand what we should copy.

- One very popular answer, in the form of an ancient story, raises as many questions as it answers:

“What is this like? It’s like an individual who was crossing from place to place and saw a structure — a castle or a fort — on fire. The traveler asks: ‘Is there no one in charge here?’ God responds: ‘It’s me.'” — Breishit Rabbah

— Is the point of this last explanation that no one else noticed the world was on fire?

— Is this like the Burning Bush (Exodus 3) where God is trying to get a human’s attention?

— Is the point that Abraham was already “crossing from place to place,” so maybe open to new ideas? One of the few things we learn about Abraham and Sarah is that they had already left their original home, Ur of the Chaldees, with Terah, before God calls.

No matter how we choose to explain “Why Abraham?” one lesson is that there’s a lot we don’t know (period).

Another is that, because there’s so much we don’t know, judging anyone else’s behavior is risky.

A third: Consider the question from inside Abraham’s family. Asking “Why Abraham?” — and then realizing there’s no simple answer — can be a reminder about how our own generations, our stories, work. We inherit a lot — ideas about the world, burdens, privileges, trauma, and skills — without any choice in the matter. Like Abraham, though, we will experience points in our lives where the question is:

Will we stay where we are or “go forth” toward something else?

Whatever we choose at those points, there will be places and people that become part of our new home. And there will be places and people left behind, stories that branch off from ours.

Managing the old and the new, as we head in new directions, will always be complicated — just as it is for the families of Genesis. One set of choices we constantly face is A) whether, and how, to continue associating with the “old” home, and B) how we talk about the folks left behind:

Do we need folks in the dropped forks to be enemies, or “wrong” or “backward,” in order for us to move in a new direction? Can a close reading of Genesis help us here?

Back to the Generations

The outline of Fork (3), summarizes the Genesis story through Chapter 25. Ishmael and Hagar are cast out, and Ishmael nearly dies (Gen 21). Isaac is nearly sacrificed (Gen 22). By the end of the portion Chayei Sarah, the stage is set for Fork (4).

Sarah dies (Gen 23:1-2) and is mourned by Abraham and Isaac. Abraham dies (Gen 25:7-10) and is buried by both Ishmael and Isaac. The twin men are both settled near Beer-lahai-roi, a place associated with Hagar’s visions.

Ishmael’s descendants are listed, with “eleh toldot, these are the generations” (see above), and he dies (Gen 25:12-18). The close of the portion Chayei Sarah is the end of Ishmael’s story. The same Hebrew words — “eleh toldot” — mark the start of Isaac’s story.

We’re back to the puzzling opening verse. of “Toldot,” discussed briefly above.

The portion opens with “eleh toldot,” which usually offers a list of descendants. Instead, we learn that the couple has no children. We are again reminded that Isaac’s father is Abraham, with all the history that includes…and all the history that goes unsaid — mentioning Abraham, but not Sarah, let alone Hagar or Ishmael. (Some Genesis genealogies list siblings.) And then we’re told that Rebecca is “daughter of Bethuel the Aramean of Paddan-aram, sister of Laban the Aramean,” stressing her connections to the “old country” or “back home.”

And, with Toldot, the first portion of the month of Kislev, we’re finally caught up with the calendar.

TORAH EXPLORATIONS: Family Struggles and Esau’s Tears

The portion Toldot begins with Isaac already married to Rebecca. The couple has no child. Isaac pleads with God, and Rebecca conceives —

“But the children struggled in her womb, and she said, ‘If so, why do I exist?’

She went to inquire of YHVH, and YHVH answered her,

‘Two nations are in your womb,

Two separate peoples shall issue from your body;

One people shall be mightier than the other,

And the older shall serve the younger.‘” — Gen 25:22-23

Rebecca aims to force this prophecy by tricking Esau, the elder twin, out of his blessing. She helps Jacob masquerade as Esau so that Isaac — whose eyesight is now “dim from seeing” — blesses Jacob in error. Learning of the deception, Esau cries a “loud and bitter cry.” He asks Isaac: “Have you not reserved a blessing for me?” And he hates Jacob (Gen 27:34-41).

Rebecca fears that Esau will kill Jacob. She tells Jacob to spend a few days with extended family, just until Esau’s anger cools, saying “why should I be bereaved of both of you in one day?!” (Gen 27:45). She then convinces Isaac that the relocation was his idea, and Isaac sends Jacob off to stay with “Laban, son of Bethuel the Aramean, the brother of Rebecca, mother of Jacob and Esau” (Gen 28:5). This is the last we hear from her.

Rebecca does not live to see the sons reconcile. Instead, her motherhood experience is squeezed between

- “Why do I exist?!” and the knowledge that she is carrying opposing nations within her; and

- “mother of Jacob and Esau” as she watches the siblings part from each other.

Some of Rebecca’s struggles might be ones we recognize —

How hard it is to be an outsider — years after being “welcomed” to a new place or family!

How heart-breaking it is to be caught between two (or more) people with contradictory needs!

When do we act, trying to fulfill God’s plan, as we understand it, and when do we trust and wait?

The whole story of Isaac, Rebecca, Esau, and Jacob seems deeply human, and relatable, in many ways. Within the bigger Genesis picture, however, the family split at Fork (4) is complicated — and still influences our world today.

Tears from a Dropped Fork

In some ways Fork (4) is similar to those that came before: The Torah will follow one fork in the road, telling the story of Jacob and descendants; the other fork, with Esau’s line, will be less important.

When the brothers meet after twenty years, Esau appears just fine, kisses his brother, says he needs nothing from him, and suggests they go their own ways (Gen 33). Esau and his descendants become one of several roads not taken for the Genesis story.

But the split is not as clean for Jacob, or for the nations the brothers eventually represent.

Jacob pretended to be Esau, in order to get the blessing. Maybe that complicates his work to separate

their identities. Twenty years after their parting, Jacob “wrestled with God and men,” was permanently injured, and received a new name (Gen 34:25-32) before meeting Esau. (See below.)

Later Jewish tradition stresses the trickery involved in Jacob getting the blessing and worries about Esau’s “loud and bitter cry.” It is taught that the Messiah, or final Redemption, “will not come until Esau’s tears have ceased to flow.”

This “Esau” is no longer the individual Bible character, son of Isaac and Rebecca, twin of Jacob. Instead, he is a symbol of estranged kin and a whole people crying out from injustice and grief. In this view, Esau is often assumed to carry an understandable grudge.

One teaching compares Esau’s story with the Book of Esther, read at the holiday of Purim.

What Goes Around

Mordekhai, a member of the king’s staff and older relative of Queen Esther, learns of the official decree to kill all Jews in Shushan. So, “he cried a loud and bitter cry” (Esther 4:1).

This is the same language used in Gen 27:34, when Esau “cried a loud and bitter cry.”

Esther Rabbah notices the matching words and relates the two stories:

“Jacob caused Esau to cry one cry. As it is

written: ‘He cried a loud and bitter cry.’

As a result, Jacob’s descendant, Mordekhai, ‘cried a loud and bitter cry.'”

— Esther Rabbah 7:13 (6th Century CE)

Esther Rabbah is arguing a version of “what goes around, comes around.” More specifically: Events in the Purim story are God’s doing, a sort of payback to descendants of Jacob for the injustice and grief Esau experienced.

“Esau’s tears” are a common theme in later Jewish teaching, taking different lessons from the long-term results of tears and injury.

One example of a teaching on “Esau’s tears” is this sermon delivered at the high holidays, shortly after 9/11/2001. Rabbi Toba Spitzer wrote —

Maybe this is what we can learn out of the depths of the tragedy we have witnessed. That redemption will come when all tears have ceased, when all sources of suffering have been repaired. Our redemption is somehow linked to the fate of even those whom we consider our enemies. Their tears and ours are ultimately not so different.

The human spirit is so large when we allow it to be.[We’ve seen people mobilize to help others amid crisis.]Let’s not squander this opportunity to make the most of what we’ve learned about ourselves, the good and the bad. Let’s name the sins that need to be named, let’s confess them together, and then let’s come together to begin to imagine a better way. Let’s dry Esau’s tears, and our own, and begin to figure out what it will take to make redemption real.

— Tears of Sorrow, Tears of Redemption,” Kol Nidrei 5762

TORAH EXPLORATIONS: Torah of Exile

At the end of Toldot, Jacob leaves his birth home to live in Paddan-aram with his uncle’s family. Rebecca suggested he get away for a short while. But he ends up living with Laban for twenty years. Commentary through the ages discusses Jacob’s time away as “exile.”The idea of the school(s) developed from an ancient attempt to fill in more unknowns.

Ancient teachers were concerned that Jacob would be negatively influenced by living away from his birthplace and family of origin.This led to another example of reading “white space” of the text — imagining what is not written: The “Torah of Exile,” taught attheAcademy of Shem and Eber(or two separate schools).

After Abraham nearly sacrifices him, Isaac disappears from Genesis for a bit. Jacob’s story also has 14 missing years. Where were Isaac and Jacob? Commentary suggests they were studying.

And where did Rebecca go, at the beginning of Toldot, when she “inquired of God”? Some commentary says visited the Academy of Shem.

These commentaries reflect the importance of learning in Jewish tradition. But it’s also interesting to ask about studies and teachers. Genesis tells us very little about Shem and Eber. But we do know a few things from the Bible text and its timeline.

Shem is Noah’s son, the one the Torah follows at Fork (2). Eber is a more distance descendant of Noah (See p.8.) Shem lived through the Flood and the conditions before it that led God to destroy humanity. Eber lived at the time of building at Babel and the dispersion after the people’s language was confused.

So, Shem and Eber had experienced disaster and trauma. Long-ago teachers decided Eber and Shem probably knew things that would help others survive tough times in strange places. The story they handed down to us says that Jacob learned “Torah of exile” in his younger years. And that helped him during the time when he was away from home and with relatives who engaged in some shady business.

Much later, Jacob teaches “Torah of exile” to his young son, Joseph. And Joseph relies on that teaching during his decades in Mitzrayim (biblical Egypt).

Torah of Exile: Then and Now

Today, some teachers use this “Torah of exile” idea to discuss how hard it is to live a Jewish life away from strong Jewish community. In addition, one author focuses on education and support for the Bible’s main characters:

“…God did not simply appear to the Bible’s heroes. They were not born with deep strength and conviction; rather, the forefathers worked hard to develop their faith. They went to seek advice from those who knew more than they. They spent time contemplating God and life’s meaning.”

— “The First Beit Midrash” 2014 Stern College

What studies and other supports help maintain a spiritual life in difficult times and circumstances? What “Torah of exile” helped Jacob and Joseph? Did Rebecca and Isaac need different kinds of support? What “Torah of exile” do Jews today need?

Torah Explorations: Becoming “Yisrael“

Fork (4), Jacob’s story, continues with the portion Vayeitzei. In it, he marries Leah and Rachel and fathers 11 sons and a daughter. This portion is rich in story and lessons (for another day).

In the next portion, Vayishlach, Jacob meets Esau for the first time in twenty years. Preparing to meet his brother, Jacob spend the night alone and wrestles with a divine being (some readings say “angel,” others believe Jacob somehow wrestles directly with God). As a result of this, Jacob gets a new name: “Yisrael,” which means “wrestles with God.”

His original name does not disappear from the Bible, though. Both “Jacob” and “Yisrael” continue to refer to the individual and to the biblical nation.**

…Later Jewish thought is full of discussion about the two names. Maybe Jacob is physical self and Yisrael is the spiritual being. Maybe one is the “best self” we aim to be eventually, and the other is today’s reality. And/or maybe the names reflect different traditions coming together in one story….

On the road back to Canaan, Jacob’s twelfth son, Joseph, is born, and Rachel dies in childbirth. The portion Vayeishev tells the story of Joseph and his brothers. Joseph is sold into slavery in Mitzrayim [biblical Egypt], is imprisoned for years, and also holds positions of leadership. His position in Mitzrayim later helps save the rest of the family from famine back in Canaan. And that leads to the Exodus story….

There is so much to explore in these portions!

Names and Nations. Both “Jacob” and “Yisrael” are sometimes used for the entire people. “Bnei [children of] Yisrael” can mean the specific children of Jacob or the whole nation. In both cases, Divrei MA uses the Hebrew “Yisrael,” rather than the English “Israel,” to avoid confusion with the contemporary State of Israel. Similarly, Divrei MA uses “Mitzrayim” for biblical Egypt.

“The Land.” Over the centuries, Jews have read Torah with different views of “the Land.” Some Jews view “the Promised Land” as an idea, or a state of being — always just out of reach — rather than a physical place. Other Jews find deep meaning in linking biblical characters and places with Jewish history and with geography today.

The abstract view has been part of Jewish thought for centuries. The Torah reading cycle reflects this idea, bringing us near, but not into, the Land. Passover is also designed around more abstract ideas. We only include four of God’s five Exodus promises: 1) I will bring you out, 2) deliver you, 3) redeem you, and 4) “take you for a people.” The fifth promise — “I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham, and Isaac, and Jacob, and I will give it to you for a possession” — is not included. Looking ahead to a Messianic Age, or final Redemption, the focus is on visions for society, not a particular location for Jews to live.

The geography-centered view has also been part of Jewish thought for centuries. In this view, the physical land is essential to Jewish history and future. This sometimes blurs the line between Bible and history. For example: argument that the biblical Abraham’s purchase of a burial site has legal implications today (portion Chayei Sarah). These views are also complicated by Christian and Muslim teachings, which overlap and contradict Jewish thought.

Conflict. Various “Land” ideas, in Judaism and other traditions, have been part of political and military conflict for centuries. Jerusalem and its relationship to “Rome” — also a specific place and an abstract concept — have been part of arguments over power and government for more than two thousand years. For even longer, people from many ethnic, cultural, and faith backgrounds have been struggling to live and build community…and fighting about resources and borders…on land that is now Israel/Palestine.

Views differ greatly about what led to the current tragedy in Israel/Palestine and how it might stop. One thing many of us share is a struggle to engage the Torah cycle at this difficult time. How do we read about places and God’s promises in Genesis, while trying to absorb the terrible news unfolding in those places today? For all who find this year’s Torah reading heavy and heart-breaking: you are not alone.

These Torah Explorations come with wishes for strength and wisdom as we wrestle together.

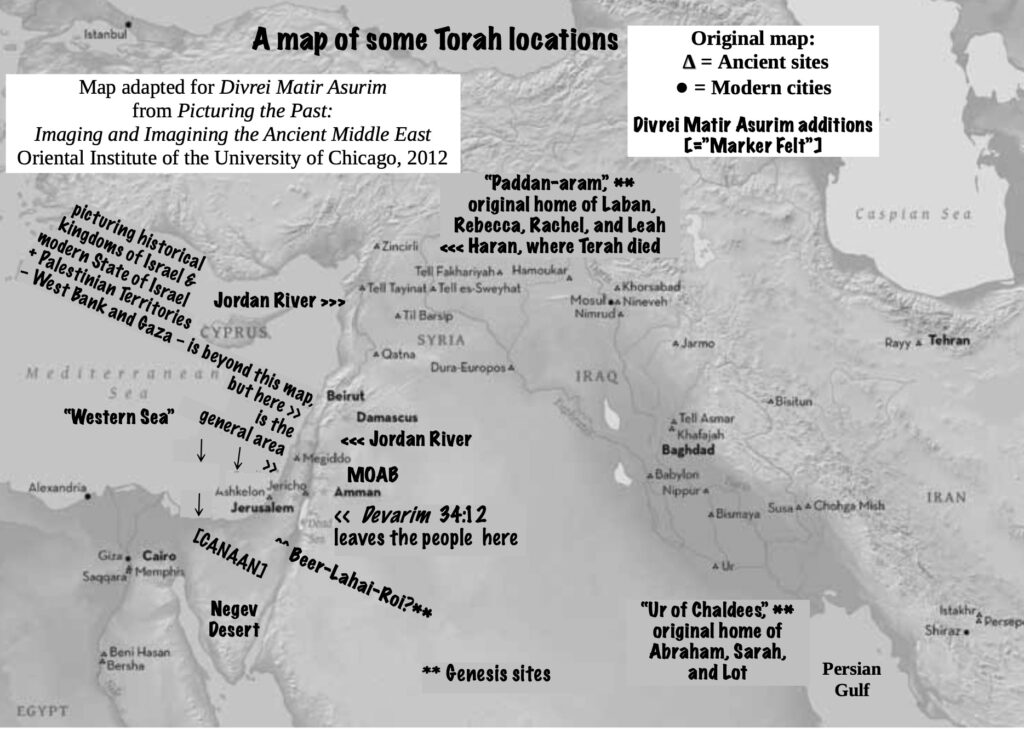

Image description: “A map of some Torah locations” Map shows present-day Egypt, Israel/Palestine,* Syria, Turkey, and Iraq plus ancient sites. It is adapted to highlight the spot where Devarim 34:12 appears to leave the people, as the Torah closes: 1) east of the Jordan River, “opposite Jericho,” facing across the Dead Sea and the Negev Desert toward the “Western Sea” (Mediterranean). The map also shows three Genesis sites: 1) Ur of Chaldees, original home of Abraham, Sarah, and Lot, near what is now the Persian Gulf; 2) Paddan-aram, at the northern tip of the Euphrates River, home of Laban, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah; and Haran, where Terah died; 3) in Canaan, Beer-lahai-roi is shown here, with a question mark, as south of the Dead Sea and north of the Negev. Additional modern and ancient sites are marked.

*picturing historical kingdoms of Israel & modern State of Israel + Palestinian Territories — West Bank and Gaza — is beyond this map [but general area is marked].

Ending on a somewhat lighter topic

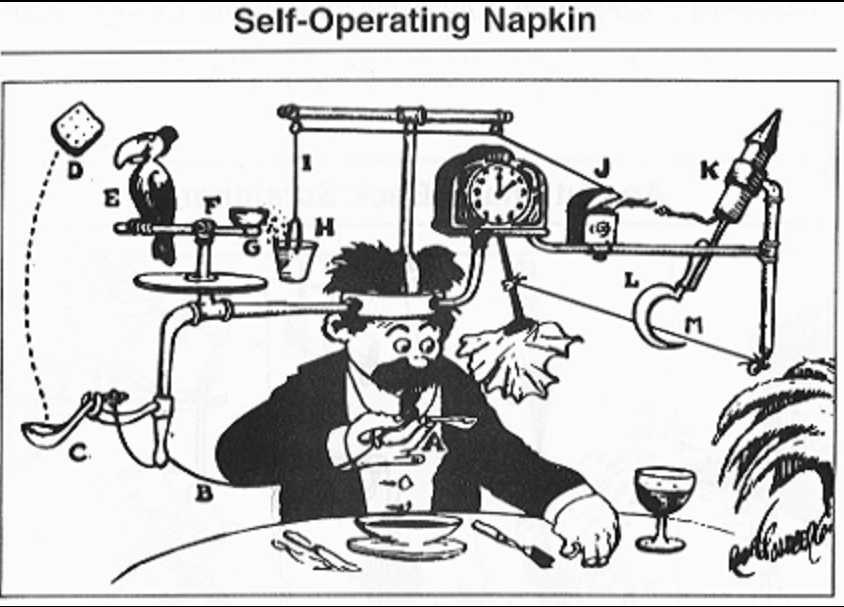

The yahrzeit of Reuben Lucius “Rube” Goldberg (July 4, 1883 – December 7, 1970) is 9 Kislev. He was a cartoonist, an inventor, and an engineer. He is probably best known for complicated contraptions designed to accomplish simple tasks.

Originally published in Collier’s 1931.

Public Domain.

The “Self-Operating Napkin,” for example, uses a string attached to a soup spoon to jerk a ladle. The ladle throws a cracker. A parrot jumps for the cracker, which tilts the bird’s perch, dropping seeds. Seeds land in a pail. The extra weight pulls a cord. That opens a lighter to start the wick that sets off a rocket. The mini-rocket launch causes a blade to cut a string. This releases a clock pendulum, swinging a napkin across a person’s chin.

Goldberg began publishing invention cartoons in 1912. Before long, his name became an English word to describe a complicated approach to simple things. “Rube Goldberg” and “Goldbergian” have been listed in American English dictionaries since the 1920s.

Rube Goldberg’s work can remind us that everything is connected, often in ways that are not obvious. Goldberg also wanted to raise questions about whether inventions were really helping individuals or society. In that spirit, we can reflect on Torah teachings to ask if they are ones that promote ethical behavior and visions. And if, not, do we need a different approach?

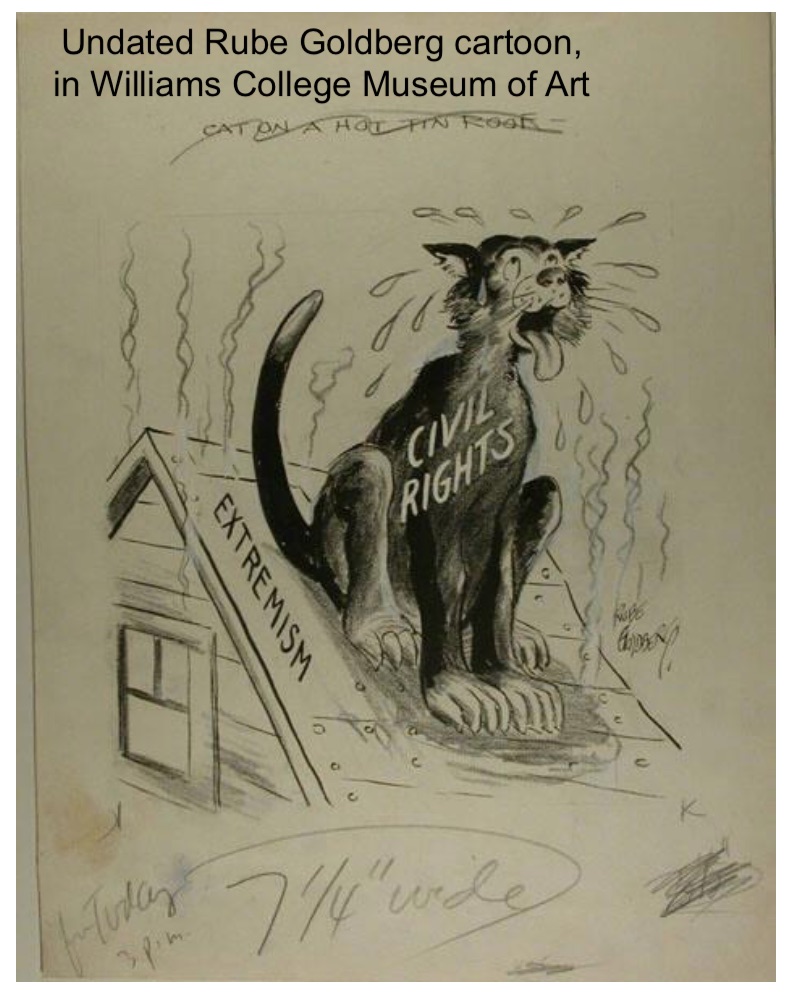

Goldberg was equally famous for political cartoons. “Peace Today” was awarded the 1948 Pulitzer Prize: A family home and patio sit atop an Atomic Bomb, tilting dangerously on a cliff edge between “World Control” and “World Destruction.” “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (left), shows a cat named “Civil Rights,” suffering from heat atop a house labeled “Extremism.” It’s undated, so it’s not clear what current events prompted the drawing, but it seems still relevant.

Undated Cartoon by Rube Goldberg.

Now at Williams College Museum of Art.

The Rube Goldberg Institute for Innovation & Creativity continues to support educational programs in his name.

“Self-Operating Napkin” appeared originally in Collier’s magazine, 9/26/31, and is now in the public domain. “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” is found at Williams College Museum of Art, Williamstown, MA.

May Rube Goldberg’s memory be for a blessing — and some laughs.

Forks in the Genesis Road (image description)

(1) Eve and Adam

>> Abel (deceased)

>> Cain marries, has a son, Enoch, and founds a city named for him. Five generations follow.

>> Seth > Enosh > Kenan > Mehalalel > Jared > Enoch > Methusaleh > Lamech > Noah

NOTE: A few descendants appear later in the Bible. (In midrash, one descendant, Naamah is Noah’s wife.) Mostly, this fork drifts off

(2) Noah and wife (Naamah)

>> Ham

>> Japheth

>> Shem > Arpachshad > Shelah > Eber > Peleg > Reu > Serug > Nahor > Terah > Abraham

NOTE: A few descendants appear later in the Bible. (The “Curse of Ham is an important, but complex, part of later Jewish and Christian thought.) Mostly, this fork drifts off

(3) Abraham

>> and Hagar: Ishmael

>> and Sarah: Isaac

Ishmael’s fork mostly drifts off in the Bible. (Ishmael is an important prophet in the Quran and Islamic teaching.

(4) Isaac and Rebecca

>> Esau

>> Jacob AKA Yisrael

>>>> Jacob’s family, “children of Yisrael,” go to Mitzrayim and settle there, leading to the Exodus story.

NOTES: In Genesis, the twins eventually part on OK terms, and then Esau’s fork mostly just drifts off.

One descendant, Amalek, appears as a permanent enemy in Exodus and Devarim and in later Jewish thought.

In later Jewish thought, Esau (Edom) is identified with the Roman Empire and Christians. This results in readings of his character as a threat and “wicked.” In common biblical commentary, everything Esau does – including kissing his brother in greeting – into something mean-spirited.

Share Your Creativity and Questions

Matir Asurim welcomes visual arts and writing, reflections on Jewish prayer and practice, words of Torah, and other thoughts on MA’s workforDivrei Matir Asurim and resources packages.

Questions. Do friends/family/loved ones have a question about Jewish practice while incarcerated? Send questions and we’ll answer in a future resource mailing. Topics might range from the meaning of a specific prayer to how to bring in the holiday when you can’t light candles, and anything in between.

Contact Matir Asurim. PO Box 18858, Philadelphia, PA 19119. matirasurimnetwork@gmail.com

Divrei Matir Asurim is a publication to promote religious education and solidarity among members and all interested.

If not otherwise noted, content is provided by V. Spatz, an outside member of Matir Asurim. As this experiment continues, look for words from other members…. and please consider sharing your own.